The Mystery of Michelangelo's 'Creation of Adam'

Created | Updated Sep 3, 2011

Without having seen the Sistine Chapel one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving.

- Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Rome 1787

The Artist's View

Imagine the artist, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, working alone, suspended high above the floor in a scaffold, lying on his back, working in a difficult medium he did not particularly care for. Yet he was already famous, and was no doubt compelled by his pride, and his artistic passion, to strive for the perfection that had earned him the well-deserved sobriquet, 'divine'.

Despite his discomfort, his well-known dislike of painting, and his desire to return to sculpting the figures for the tomb of Julius II, within the space of four years this incredible individual painted some 300 figures, adorning more than 5,800 square feet of the St Peter's Sistine Chapel ceiling with a stunning masterwork beyond what many could achieve in a dozen lifetimes1.

A New Perspective

If you have an opportunity to view some recent reproductions, or the good fortune to view directly these newly cleaned and restored magnificent frescoes, allow your gaze to linger just a bit longer on The Creation of Adam. There are many very good websites devoted to this particular fresco, and there is a particularly excellent 'virtual tour' of the Sistine frescoes available at the Web Gallery of Art - Sistine Chapel Tour.

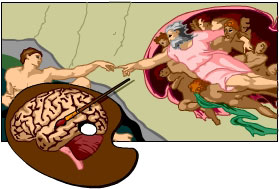

Viewed purely as a singular work of art, this scene, unnamed by the artist, is arguably one of his greatest masterpieces. Reproduced in countless art books, posters, and postcards, it has become one of the most well-known images in the world. And now, some 500 years after Michelangelo painted it, an astonishing theory provides an entirely new perception of the work, and perhaps an insight into the mind of its creator.

In the fresco traditionally called the 'Creation of Adam', but which might be more aptly titled the 'Endowment of Adam', I believe that Michelangelo encoded a special message.

- Frank Meshberger

An interpretation of Michelangelo's Creation of Adam Based on Neuroanatomy (JAMA 264:1837-1841, 1990)

What is usually interpreted from this particular scene is that Adam is not being physically created, but is in the process of receiving something momentous, yet subtle, from the hand of God. Adam's languid posture appears to be one of near mindless repose, whereas the figure of the Creator fairly bristles with energy. The composition enables the viewer almost to perceive the passage of a spark jumping the gap between the outstretched, not quite touching, fingers.

It may be that some residual spark persisted over the centuries, to eventually ignite the inspiration of Frank Meshberger, medical student, idly paging through a book about Michelangelo, relaxing after hours of intense study in the neuroanatomy lab at the Indianapolis School of Medicine.

As he gazed at a three-page foldout colour reproduction of the 'Creation of Adam,' he was...

... immediately struck by the shape of the image surrounding God and the angels. It was the same thing I had been working with all day! It was the unmistakable outline of the mid-sagittal cross-section of a human brain.

- ibid

At first, he noticed that the swirling green robe corresponded with the vertebral artery, which follows an irregular path upward toward the pons. Then he noticed the angel's leg extending below the base of the pink outline that matched the anterior and posterior pituitary. The angel's foot was depicted as bifid, in two parts rather than five toes. Then he noticed the general outline of the sulcus, and the fissure of silvius, which separates the frontal from the parietal lobe.

Although mildly intrigued at the correspondence between the fresco and the brain cross section, he assumed it was not unknown. Regarding art history trivia as irrelevant to his chosen profession, he went back to his studies, eventually graduating and opening a private practice as an obstetrician/gynecologist. Occasionally, he would casually mention his observation to friends, but it was not until 1988, when the Sistine Chapel fresco restoration project was well under way, that it dawned upon him that apparently no one else had ever made a similar observation.

His curiosity piqued anew, Dr Meshberger began researching the life of Michelangelo, and nowhere found any reference to the outline of the human brain on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. He superimposed a transparency of the fresco on a drawing of the sagittal cross section of the brain. The conformity was uncannily, eerily precise:

Until I looked through the transparency I didn't realise that one of the angel's backs was the pons, that the legs and hips were the spinal cord... The knee of the flexed right leg of the angel with the bifid foot represents the transected optic chiasm, the thigh the optic nerve and the leg itself the optic tract...

- ibid

Anatomy of a Master

No one could doubt Michelangelo's technical skill, his artistic genius, or his obvious familiarity with gross human anatomy. But how was it possible for even a Renaissance Master to acquire such an intimate knowledge of human neuroanatomy, particularly the human brain?

For the church of Santo Spirito in Florence, Michelangelo made a crucifix of wood which was placed above the lunette of the high altar, where it still is. He made this to please the prior, who placed rooms at his disposal where Michelangelo very often used to flay dead bodies in order to discover the secrets of anatomy.

- Giorgio Vasari The Lives of the Artists, translated Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991)

Religious Symbolism, Philosophy, or Humour?

Scholars and art historians have long recognised that Michelangelo habitually made liberal use of symbolism in both painting and sculpture, and perhaps he was also fond of visual puzzles and humour2. For example, the 'supporting cast', and the accompanying embellishments, (the nude figures, the prophets and sibyls3, the scenes in the medallions4 and spandrels5), which adorn the Sistine Chapel ceiling, have never been satisfactorily interpreted.

There is some speculation that much of the symbolism attributed to Michelangelo's works is due not only to the cultural and religious climate of Florence in the 1480s and early 1500s, but also the philosophy of Neoplatonism. There is evidence that at the time of painting the Creation of Adam, Michelangelo was influenced by the Neoplatonic teachings of Marsillio Ficino (1433 - 1499), and Pico della Mirandola (1463 - 1494). His writings and poetry of that time reflect his belief in the divine origin of art, and of physical beauty, and that the intellect is itself divine.

The outline of the human brain in the Creation of Adam may then be interpreted as the artist's pictorial declaration of his belief equating the divine gift of intellect with that of the soul.

However, since one of the axioms of Neoplatonism is an insistence that none of the really important truths, such as the concept of God, can be communicated by conceptual means, a reciprocal interpretation is just as valid: perhaps Michelangelo is expressing his belief that any human concept of God is necessarily inadequate, and any image of God is thereby a creation of mind; in this case, the mind of Michelangelo.

The Mind's Eye

Or perhaps neither interpretation is accurate. The image of the brain on the Sistine Chapel may be no more than a trick of perception, similar to our imagination causing us to see figures in the clouds; faces on the wall-paper. The fresco's resemblance to the cross-section of the human brain may be a message not from the great artist, but from our own minds.

For centuries, the significance of the Sistine Chapel paintings has been analyzed by historians, dissected by critics, and debated by theologians and intellectuals, most of whom were content with the 'obvious' interpretation of the Creation of Adam scene. Cleaning and restoration has reawakened interest in the frescoes, and Dr Meshberger's analysis of this individual image impels an even closer look, adding yet another dimension to the mystery.

Quite likely Michelangelo would have enjoyed the speculation and controversy engendered by his work, and if asked to explain his motives, and the symbolism of his creations, would have kept an enigmatic silence.