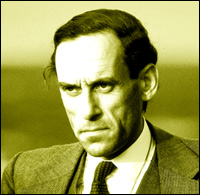

Jeremy Thorpe - Former Liberal Party Leader in the UK

Created | Updated Jun 13, 2011

British MP Jeremy Thorpe is the Liberal Party leader that many people would rather forget. Forced to resign the party leadership in disgrace with a legal case hanging over his head, he lost his seat during the election that saw Margaret Thatcher sweep to power, and never returned to frontline politics. That he was later fully exonerated by the court makes the case all the more frustrating for the man who at one time might well have been the Liberal Party's best chance for power.

From Saviour to Scandal

John Jeremy Thorpe was born on 29 April, 1929. He was the son and grandson (on his mother's side) of Conservative MPs, but in his youth he became involved with the Liberals, which changed his political viewpoint somewhat. Thorpe had a classical education, attending Eton College before going up to Trinity College, Oxford. He was one of many politicians who served as President of the Oxford Union. He studied law and was called to the bar in 1954. He was famous for wearing a brown trilby hat and large Liberal rosette when out on the stump.

In 1959, Thorpe stood for parliament as a Liberal, winning the seat of North Devon. He was at the time one of a dwindling number of Liberal MPs and in 1967, when Jo Grimond resigned as leader, he won the subsequent leadership election. Grimond had been a firm hand on the rudder of the smallest mainstream party in British politics, and it was often speculated that he might have been a contender for Cabinet office had he represented one of the other two parties. Thorpe however brought a youthful, dynamic element to the leadership that was much needed. Though Thorpe was often upset that the press labelled his approach as all gimmicks with no substance, during one election he did a tour of the south coast by hovercraft; unfortunately the English weather limited the photo opportunities.

As with most Liberal MPs of the time, Thorpe's seat was far from secure, however he had a loyal personal following in North Devon during his time as MP. He was capable of drawing large crowds to his public orations that were filled with a mixture of humour and passion. In 1964, he was returned with a majority of 5,136 over the Tories who were determined to win back this seat. 1966 saw his majority eaten into; he managed to defeat the opposing Tory candidate by just 1,166. At the next election, in 1970, he was nearly knocked out as leader, managing to raise a slim majority of 369. By the first election of 1974, the Liberal Party were enjoying a brief revival in popularity and Thorpe was 11,072 votes ahead of the field; sadly the second election that year, in October, saw Thorpe's lead drop to just 6,721.

Thorpe was married to Caroline Allpass, with whom he had one son, but Caroline was killed in a car crash just after the election in 1970. He then married Marion (nee Stein) who was the divorced former wife of George Lascelles Earl of Harewood1. She was the daughter of a Viennese music publisher and was an accomplished concert pianist.

However in 1976, Thorpe found his career brought to a sudden and messy end when he was embroiled in accusations of having conducted a homosexual affair with a former model - and allegedly threatening the model's life.

The Scott Affair

In 1975, former model Norman Scott, made allegations that he'd once had a homosexual affair with Thorpe back in the early 1960s. Of course, at the time the affair - which Scott claimed had begun in 1963 and ended in 1963 - homosexuality was still a criminal offence and Thorpe was a member of the House of Commons. Scott also claimed that Thorpe threatened to kill him after the alleged affair had been made public, specifically that Thorpe had incited David Holmes, deputy Treasurer of the Liberals, to murder Scott. To prove his case, Scott sold to the tabloid press some letters that he claimed were from Thorpe. Though Thorpe denied the allegation, the revelations still forced his resignation of the party leadership. Jo Grimond returned as caretaker leader until party elections put David Steel in charge a few months later.

On the day he was formally charged at Minehead Magistrates Court, Thorpe attended a coffee evening with the local party, accompanied by his wife. They fought their way through a media scrum to the event. Though tickets to the event cost just 50p, there was a large, clear notice on the door that read: 'No Media'.

The 1978 court case revealed that Thorpe had allegedly told his fellow Liberal MP Peter Bessell of the situation and said (referring to Scott): 'We have to get rid of him'. The prosecution also claimed that local garage owner George Deakin was also implicated in the plot in some way. Another source alleged that an airline pilot called Andrew Newton was paid £5,000 from Liberal party funds to carry out the murder2. Scott also made out that he had been an unwilling partner in the affair in the 1960s, being subjected by Thorpe to sex acts that infamously caused him to 'bite a pillow'.

The trial, unsurprisingly, took place under the glare of the media; Thorpe had, after all, been the leader of a major political party. However, after a month of court proceedings and deliberations, Thorpe was acquitted of the charge of conspiracy to murder Scott. As to the implicit allegations that he had been involved in homosexual behaviour at a time when it was illegal, nothing more was ever said. Certainly Thorpe himself has never made any public statement concerning his sexuality.

Wilderness

Little more has been heard of Jeremy Thorpe since his virtual exile in the aftermath of the 'not guilty' verdict. Indeed, it has been noted that while his peers seemed happy to ensure he did not go to jail, they were less content to see him return to the prominent place in society he had once enjoyed. In 1999, however, a group of Liberal MPs launched a campaign to nominate Thorpe for a Life Peerage, though ultimately nothing came of it. In 2001, he emerged briefly during the 'Foot and Mouth' crisis to call for an aircraft carrier to take the backlog of animal carcasses out to sea and dump them there; a farm in his home of Barnstable had been affected by the horrific disease.

Shortly after the trial that ended his career, Thorpe faced even greater distress when he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. For the many who still remember him as a once great statesman, it was some small comfort to see him still fit enough to attend the funeral of fellow former Liberal leader Roy Jenkins in 2003.