The Virtual Reinhard

Created | Updated Mar 3, 2002

A Letter from Martinique

The Jumbo 747 lifted off from Paris en route for the Caribbean, and we were on our way on my first trip across the Atlantic. I knew that, whatever happened, the forthcoming week on the island of Martinique would throw up the unexpected.

It didn't take long for the first surprise. I had been watching the ocean roll past below, marvelling at the sheer size of it and appreciating personally for the first time the well-worn fact that the planet is two thirds under water. After nearly four hours of flying, a tiny island passed below, The Azores and the first sighting of land since France. It was then, noticing a small fishing boat nosing in under the volcano, that I realised that this was the first boat that I had seen. I'm used to the English Channel, and I had always taken with a pinch of salt the tale that it is the busiest shipping lane in the world, but now it all sunk in. Oceans are big.

Another three hours passed before any new obstruction broke the endless wrinkled surface of the sea. Dusk was falling as the plane descended, and the lights of fishing villages twinkled around the edges of the island below. This tiny lump of volcanic rock, forty miles by ten, was to be our playground for the next seven days.

There were no customs formalities, as despite it's Caribbean location, Martinique is officially part of France. It took only a moment to get some money and hire a car, and then it was off into the night to find our apartment, ten miles and half an hour away, on the south coast in the town of Diamant. The water pump seemed to be squeaking loudly, and it was only after some discussion about whether we should return the car to the hire centre that we realised that the noise was actually the grenouille and other insects singing in the trees. This sound was to become part of our life during every unlit hour, and would often be deafeningly loud, although curiously restful at night.

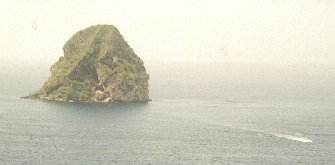

Diamant was easy to find. It is dominated by a huge rock sticking out of the sea, locally know as La Diamant but regularly saluted by the British Navy as HMS Diamant Rock, in remembrance of earlier times when it was garrisoned against the French.

The next morning set the pattern for the days ahead. Hummingbirds joined us for breakfast on the bushes by the patio, startling the jewelled lizards which scurried away amongst the blossoms. Small flocks of merle, ubiquitous birds the size of blackbirds with the manners of a sparrow, squawked and shrilled in a continual bid for table scraps. The palm trees waved in the breeze, and a few early risers splashed in the pool. This was really the life.

The island of Martinique is part of the volcanic chain that is the Windward Isles. The northern half of the island is dominated by the active volcano Mt Pelee, almost permanently shrouded by the cloudcap that nourishes the luxuriant rainforest around it's flanks. From the resort village of Diamant in the south, it takes three hours to drive the tortuous forty miles through the forests and plantations, but we did it again and again. This is the spine and lungs of Martinique; all else is froth cast up from the sea.

The rain forest was a magical place. The trees, already immensely tall, are given extra stature by the sixty-degree slope of the volcano. The canopy is far, far above, and it is clear that this is where the action is, not down in the darkness with the dead things and the scavengers. Not even rain makes it unimpeded through the canopy. First it is caught by innumerable funnels and gutters, channelled into reservoirs and into the waiting roots high above. Only the surplus falls to the ground in grudging little splatters, just part of the continual rain of falling debris... dead leaves, twigs, corpses of small animals, seeds and fruit.

There is no middle ground. High above, the tree canopy. Down on the ground, poking optimistically through a century's leaf litter, are all the low-growing plants, a mere ten or so metres high, their flowers serviced by hummingbirds and their branches scurrying with lizards.

'Jewelled' is an overworked term, but it is the only word that covers the iridescent green of the hummingbirds, the fantastic blue of the Morpho butterflies, and the vibrant lime of the lizards. Jewelled, every one.

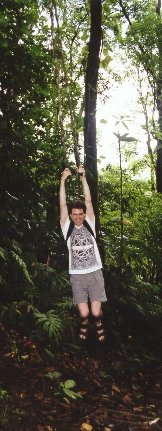

Between the upper canopy and the lower scrub were only the lianas, vine-like roots heading optimistically for the forest floor. These were incredibly flexible, although clearly made of wood, and easily strong enough to support a grown man swinging through the underbrush. I really hadn't believed that the old Hollywood staple had a basis in fact.

The humidity was incredible. The only advice given to mad foreigners insistent on wandering was to take plenty of water. We'd packed several litres of water and another of fruit juice, but it was not really enough. Sweat poured continually from our bodies as we climbed up and down the lush verdant valleys, keeping the sea on one side and the brooding heights of the volcano on the other. It was alleged to be six hours to Precheur, the next village. We came across one traveller coming the other way who said that we could hire a boat that could returned us to our car, but he was staring-eyed with heat exhaustion and was wandering in circles when we found him. Without our directions, carefully repeated like a mantra, I doubt that he would have got out before nightfall.

The volcano had other attractions too. On one occasion we toiled up the endless lava flows to the crater, only to discover that even if the path into the caldera hadn't collapsed, then the view at the top from inside the dense wet cloud was less than exciting.

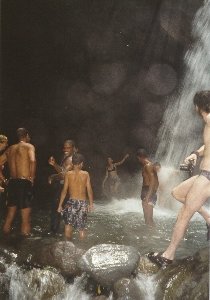

A more exhilarating route was up a series of gorges. Guides take you in swimming costumes up the waterfalls, guided by ropes up the worst bits. They supplied waterproof buckets to keep your cameras in, and it was pretty touristy but quite jolly for all that. The journey terminated in a cave full of guano and dead bats behind a huge waterfall that we took it in turns to stand under - for the few seconds before it smashed you to your knees.

There is a third route up the volcano that allegedly ends in a complex of hot springs and waterfalls, but we were thwarted on both our attempts to find it. On one night a huge and extremely angry torro had no intention of letting us past his cows, and on our second attempt the river-bed that formed the only path became distinctly hazardous after a mountaintop storm threatened a flash-flood. Maybe next time.

Nestling under the volcano is the sleepy fishing village of St Pierre, scattered with the levelled ruins of it's past glory. There was supposed to be a good museum of vulcanology, but we never did manage to find it. It would have been interesting, because until 1902 St Pierre was the capital of Martinique, but then Mt Pelee erupted and destroyed the entire town and all 30,000 inhabitants. Popular legend has it that only one man survived, a drunk who had been thrown into a small cell for the night, one of the few buildings left standing. At any rate, P.T. Barnum snapped him up for his circus, though I'm not sure what the poor man made of his life in a freak show.

When Martinique was a slave colony, much of the island was given over to sugar cane. These days, there is more profit in bananas and pineapples, but many of the old colonial cane houses and rum distilleries still stand. In fact, there are an incredible number of family-run rum companies in such a small space. Many are open to the public, and often the machinery is more or less original... steam power is common. Rum manufacture is a much simpler affair than the complex procedures for whisky or brandy. Mash up the sugar cane, chuck in some yeast, distill it and then, if you want dark (vieux) rum, keep it in a wooden barrel for a few years. The results are wonderful, completely unlike the stuff we see in Europe. Understandably, the locals sneer at the big commercial outfits, who make their product from the waste from sugar factories.

Rum is drunk everywhere, at all times of day, but never to excess. Traditionally it is served mixed with a little cane syrup as Ti'punch, but it also mixes with any of the bewildering array of fruit juices commonly available.

Rum and fruit are also main constituents of the ubiquitous creole cuisine, adding flavour to an enormous variety of fish. The seafood is incredible. The langouste are the size of lobsters, and often as long as a man if you include the antennae, and a fish is not worth serving unless it's head and tail overlap the side of the plate. To counterpoint the fish dishes, most places offer colombo, a sort of curry or stew, and everything is served with bananes jaune, savoury bananas that are out of this world. In fact, all of the fruit has a depth of taste that is completely missing from European imports, with the added cachet that although you can buy it at the market for a few francs, it is almost as easy to pick it up from the roadside. There are fallen coconuts and fruit everywhere, just lying around for the taking. As far as I can see, there is no reason to ever starve on Martinique.

Most of the island is dedicated to fishing and farming, but in St Anne big business has arrived in the form of a Club Med complex. We went over there one day because the watersports are heavily advertised, hoping to hire a boat or some jetskis, but we were thoroughly put off by the Mediterranean-level prices and, incredibly, a charge just to get onto the beach. We had a look about but escaped to the sanity of the island as quickly as we could. In nearby St Lucia, for the price of an hour's Jetski hire, we arranged a whole afternoon's scuba-diving on the reef.

That was a great experience. The corals were beautifully healthy, and teeming with shoals of multicoloured fish. Great fans of Gorgon coral splayed up from the seabed, sheltering six-inch sea urchins and supporting the bizarre Flamingo's Tongue sea snails. Everywhere there were doctorfish, pipefish, trunkfish, and immense mixed shoals, all completely unafraid and often curious enough to try nibbling your fingers.

All too soon the dive was over, but we knew where the reef was now, and much of it was in easy snorkelling distance. On subsequent explorations I encountered... and avoided... barracuda lurking just beneath the surface, and some kind of sea-snake wriggling along on the sandy bottom. Above our sunburned backs soared the huge fork-tailed Frigate birds, the only seabirds that we saw the whole week, though Diamant Rock is supposed to be a famous seabird sanctuary.

And, of course, there were the crabs. These amazing crustaceans had filled almost every ecological niche. Far inland, miles from any water, we came across the ubiquitous land crabs, especially the hermit crab known locally as Bernard l'Hermite. Some lived in old land-snail shells, but the big ones especially had got hold of big whelk shells which they must have dragged all the way up from the sea.

Everywhere we went, the ground was riddled with the burrows of several different species of land crab, all brightly coloured in red and yellow and green, some tiny, others bigger than your hand, all moving extremely quickly when disturbed. Seemingly without natural predators, these were the true owners of Martinique.

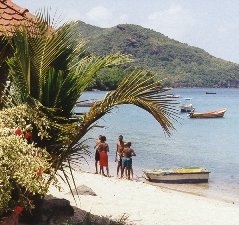

On the last hour of the last day, we sat on a wall high above the sea, drinking local Lorraine beer and watching the sun set over the fishermen positioning their nets over the coral reef. The youngsters eased the brightly-coloured wooden boats forward and back on the shouted instructions of their father, duck-diving down to the reef to check that all was going to plan. Some things on this island have never changed, and I hope they never will.