Oceans: the Sea Floor

Created | Updated Nov 9, 2008

The deep ocean floor was once thought by scientists to be flat, but modern sonar equipment has revealed that it is no more flat than the continents are. The ocean floor is dotted with seamounts, many of which are higher than Mount Everest, and trenches, the deepest of which is called the Marianas trench.

Description

The vast underwater world begins with the shallow continental shelf which surrounds all landmasses. This shelf is made up of rocks slightly less dense than the underlying oceanic crust. They vary in width from almost zero up to the 1500km-wide Siberian shelf in the Arctic Ocean. The shelf slopes gently down to about 200m, where it suddenly drops with a steeper gradient of about 4 degrees. This is called the continental slope. After this drop is the continental rise which isn't actually a rise, just a continuation of the continental slope with a gentler gradient - of usually less than 1 or 2 degrees. It is made up mainly of fallen sediment from the continental shelf. At the depth of between 3700 and 5500m, the abyssal plains begin — no sunlight penetrates here and only sea creatures that can handle the darkness and pressure and can take advantage of the process of chemosynthesis can survive. The oceanic crust is thinner than the crust on the continent - generally about 5km compared to 35km on land.

Formation

The ocean floor is formed by a process called sea floor spreading. The earth's crust is split up into plates which move about on top of the mantle1. They diverge, or move apart, in the middle of oceans and magma2 from the mantle rises up to form new crust. The lava that emerges billows out to form round blocks called pillow lava. An example of where this happens is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The rate of spreading varies from 2-4 cm/year at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, to 10-17 cm/year at the East Pacific Rise. At other places the plates move towards each other, or converge. If a continental plate and an oceanic plate meet, the denser oceanic plate moves, or subducts, under the continental plate which destroys crust. This forms ocean trenches which are the deepest parts of the oceans.

Features of the Ocean Floor

These processes form a number of features on the sea floor. The abyssal plains themselves are relatively barren and featureless as sediments are deposited very uniformly allowing the surface to be nearly flat. However, abyssal hills occur where the sediment is not thick enough to cover the underlying basaltic rock of the ocean crust completely. These hills are usually low and oval-shaped.

These are different to seamounts which are isolated volcanic mountains scattered across the ocean floor, often forming islands. They usually have gradients of about 20-25 degrees and generally rise more than 1,000m above the sea floor. Many surpass even the largest land mountains3. An example is the island chain that includes Hawaii. Sometimes the action of plate tectonics moves the seamount and the ocean crust sinks, pulling the island below the surface. These submerged, often flat-topped seamounts are called guyots.

Ocean trenches, produced where plates are subducting, are one of the most striking features of the Pacific floor. They have lengths of thousands of kilometers, are generally hundreds of kilometres wide, and extend 3 to 4km deeper than the surrounding ocean floor. The deepest of these is called the Marianas Trench. Located in the Pacific Ocean just east of the Philippines, it is 10,294m below sea level - 1444m deeper than Everest is high.

In 1977 scientists discovered hot springs at a depth of 2.5km on the Galapagos Rift off the coast of Ecuador. These hot springs, also called geothermal vents, or smokers because they resemble chimneys, spew out dark mineral-rich fluids, heated to temperatures of up to 380 degrees C by contact with the newly-formed ocean crust at the spreading ridge. The water does not boil because it is under so much pressure from the tremendous weight of the ocean above and when the pressure on a liquid is increased, its boiling point goes up. Smokers can be black, white, grey or clear, depending on the type of material ejected.4

Life on the Ocean Floor

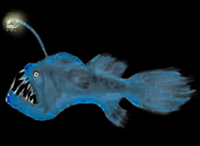

Manned submersibles such as the Alvin have now established that life actually does exist in the deepest of trenches on the ocean floor. Exploration in the pitch-black environment has revealed extraordinary forms of marine life that thrive around hot springs. The primary producers5 in these areas use the hydrogen sulphide contained in the volcanic gases that are spewed out of hydrothermal vents to live. They are called chemoautotrophs. Thus the energy source that sustains this deep-sea ecosystem is not sunlight (photosynthesis) but energy from chemical reaction (chemosynthesis). Many bizarre creatures such as giant tube worms, blind shrimp, angler fish, lantern fish, giant clams, pink sea urchins and sea cucumbers manage to survive here without sunlight in conditions of high pressure, steep temperature gradients and levels of minerals that would be toxic to animals on land. This alien underwater environment may well resemble the places where life on earth first began.

However, deep sea creatures are not only found at hydrothermal vents and scientists have long wondered what might be sustaining them at other areas of the ocean floor. The answer may lie in whale carcasses which fall to the ocean floor from above when the creature dies. Whale bones are rich in sulphur so once the flesh has been stripped by scavengers such as hagfish (primitive, eel-like fish) which can take less than six months, the chemoautotrophs can use the sulphur for years to come. One square yard of bones can sustain over 5,000 animals representing over 170 species.

Uses of the Ocean Floor

Humans have always used the oceans for food, recreation, minerals, transport, waste disposal, water and energy. As we learn more about the ocean floor we can make more and more use of it.

Sands and gravels can be taken from the shallow continental shelves and used either for construction or to protect beaches from erosion. Extensive deposits of petroleum-bearing sands have been exploited in offshore areas, especially along the Gulf and California coasts of the United States and in the Persian Gulf.

The world's oceans, particularly those off the Skeleton coast of Namibia, have much higher concentrations of diamonds than on land. From 1961 to 1970 one company was able to extract 1.5 million carats of diamonds from the ocean floor.

Research is currently being conducted to explore the commercial viability of mining nodules of manganese, nickel, copper and cobalt which form on the ocean floor around a nucleus of rock or shell. They are a potentially rich resource but it is very expensive to bring the ore to the surface.

Another resource found on the ocean floor, beneath some of the sediments deposited there, is methane clathrates. These are a form of water ice which contain a large amount of methane. They are thought to originate from gas coming from geological faults which crystallises when it comes into contact with the cold seawater. They could be an important source of fuel; however, they could also contribute to the greenhouse effect if disturbed, as methane is a greenhouse gas.

The ocean floor has long been used by scientists to determine past climatic changes. Over time, microscopic aquatic organisms called foraminifera build up on the ocean floor. Some are particularly sensitive to temperature so scientists can study ocean cores and determine that at times where there were high numbers of foraminifera the water must have been warm indicating an interglacial period, and at times when there were fewer foraminifera, the water must have been cooler indicating a glacial period.