Benjamin Britten's War Requiem

Created | Updated May 13, 2013

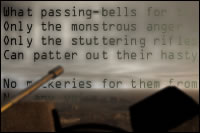

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries for them from prayers or bells,

Nor any voice of mourning, save the choirs, -

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells...

- Wilfred Owen, 'Anthem for Doomed Youth'

The 20th Century saw a great renaissance of British composers, and Benjamin Britten is widely held to be one of the greatest of them all - probably the greatest British-born composer for more than 200 years (since Purcell died in 1695 and Handel, who became British, but was born in Germany). The War Requiem, a huge choral symphony with an international reputation, is undoubtedly one of his greatest works.

The Great War

At the turn of the 20th Century, English composer Sir Edward Elgar was still going strong and producing some of his finest mature works. His great oratorio The Dream of Gerontius appeared in 1900. Elgar was rooted in the great Victorian certainties. In his day, devout religious faith went hand-in-hand with unquestioning loyalty to the ideals of king and country, empire and glory, and pomp and circumstance.

However, everything changed with the horrors of the Great War (1914-1918). On all sides of that terrible conflict young men - often just boys - were sent to a horrific slaughter, shot, blown to bits or gassed in the mud and snow. Among them were poets, such as Isaac Rosenberg (1890-1918) and Wilfred Owen (1893-1918). It is the poems of Wilfred Owen (killed in action just one week before the signing of the Armistice) that figure in Britten's War Requiem.

Benjamin Britten

Britten grew up in the long shadow cast by that war. He was born in 1913 and started composing at the age of five. He is probably best known around the world for his operas, including Peter Grimes, Billy Budd and Death in Venice. However, he was a prolific composer in all genres - choral, solo vocal, instrumental, orchestral and chamber music - and was a gifted pianist and conductor, too.

It is well known that he had a close long-term relationship with the tenor Peter Pears, and much of his writing for the tenor voice - including the tenor part in the War Requiem - was written to suit Pears's vocal qualities. In fact much of his other vocal work was composed with either Pears or another specific singer in mind.

War and the Loss of Innocence

Britten was a lifelong pacifist and the War Requiem is about the brutality and futility of war, along with the senseless suffering and monstrous death and destruction that it brings. A constant theme in Britten's works (especially in the operas) is loss of innocence, and this theme pervades the War Requiem, too.

Some time before he started work on the War Requiem, Britten had worked on two other projects which may have prepared the way for it. One of these was an oratorio, Mea Culpa, about the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945; and there was a work in progress in commemoration of the assassination of Gandhi in 1948. As it happens, however, both projects were dropped for one reason or another.

The War Requiem was commissioned to celebrate the consecration of St Michael's Cathedral in Coventry (UK) in May 1962. During the Battle of Britain in the Second World War, the cathedral and much of the city of Coventry were destroyed in one terrible night of German air raids. A new cathedral was immediately planned and, after the war, one was built next to the ruins of the old. The War Requiem was written in 1961, the year of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and the escalation of US involvement in Vietnam.

The Requiem Mass

The Requiem Mass is the votive Mass for the dead. It is basically the 'ordinary' Mass with joyful sections such as the Gloria and Credo replaced with some sombre sections. The name comes from the text of the opening section, the Introit:

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine,

Grant them eternal rest, Lord,

et lux perpetua luceat eis

and let perpetual light shine upon them.

It is an act of piety to have a Requiem Mass said or sung for the repose of the soul of the departed, since it is believed that this will assist the soul on its journey in the hereafter. Naturally, many composers throughout Christian history have written music for the liturgy of the Mass. It was JS Bach, however, who first composed a non-liturgical musical setting for the mass. His great Mass In B Minor is really a 'concert' Mass (though not a Requiem) which is nearly always performed, whether in church or concert hall, outside of the liturgy.

Many composers have set the Requiem Mass to music, and these settings are usually for orchestra, solo voices and chorus. Probably the best-known are the Requiems of Palestrina, Victoria, Mozart (written on his deathbed and unfinished), Cherubini, Gossec, Schumann, Dvorák, Bruckner, Verdi, Berlioz and Fauré.

Beethoven wrote a number of concert Masses, but no Requiem. Brahms departed from tradition by setting passages from the Bible rather than the liturgical text of the Mass, but in German rather than in Latin. His is therefore called A German Requiem. Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius refers to the people left behind on earth praying for the soul of the departed. It is not a Requiem Mass, however, but a setting for a religious poem about the soul's journey after death.

Britten's Version of the Requiem

In his War Requiem Britten does use the traditional Latin texts, but in the imaginative and innovative way of a genius. He intersperses the traditional liturgy with English poems (by Wilfred Owen), thus creating a tension between the accepted traditional pieties and the modern perspective of death.

Britten's War Requiem is angry, unsettling, often dissonant (though not atonal1), and thought-provoking. It also has passages of great tenderness and lyricism. In this way it contrasts the ugliness of war with the beauty inherent in mankind. It ends quietly but inconclusively, offering no easy comfort or simple answers.

The traditional Mass conveys the ultimate promise of salvation; but Britten wanted to bring that promise right up close against a 20th Century poet's despatch from the front line - an uncompromising message of despair, futility, bitterness, anger and disillusionment.

Some of Britten's Techniques

Rhythm

Britten is a master of orchestration and compositional technique, and uses various means to create the intended emotional impact.

His use of rhythm is at times highly complex, with different groups of musicians playing different rhythms at the same time. His purpose here is to point up the contrasts between the different groups in the tableau which he is painting.

At other times the rhythm is quite sparse and simple but unsettling, as in a number of passages where the beat is seven to the bar rather than a more regular six or eight to the bar. The effect is often heightened here by syncopation (accentuating the weak rather than the strong beats).

Heterophony

A technique which, to Western ears, sounds even stranger than complex rhythm, is heterophony. The word was originally coined by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, but heterophony figures mainly in Asian music, particularly in Southeast Asia. Britten was extremely interested in oriental musical forms, instruments, scales or modes, and so forth, which influenced much of his own music. He introduces heterophony into the 'Sanctus' section of the War Requiem.

Here the chorus divides into eight sections, with each section chanting the same words but at different pitches and not necessarily at the same time as each other. It's rather difficult to describe in words - you have to hear it.

Contrary to all the usual traditions of choral singing, individual voices are not to be synchronised here, not even with the other voices in the same section of the choir. Yet the whole passage must follow a subtle but definite rhythm. The orchestra plays ('accompanies' would be the wrong word here) in a series of trills and tremolos, and for this to make sense the orchestral line has to link up at certain points with the free chanting.

The words Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua ('Heaven and earth are full of your glory') are repeated seemingly incessantly, becoming an increasingly manic mantra, with different voices entering and leaving the flow of sound at different times.

The whole passage starts very quietly, and gradually builds up to an almighty fortissimo climax - followed by a complete silence. Then the chorus lunges into a brilliant 'Hosanna' section. It's quite amazing.

The Tritone

Another of Britten's devices is used right at the start of the War Requiem and permeates the whole work. This is the tritone. In music, an interval means the difference in pitch between any two notes 2 . The tritone is an interval of three whole tones. (Bafflingly, this is also known as an 'augmented fourth'.)

The tritone does occur within the ordinary major or minor scale, and if you can hum or play a standard scale of doh ray me fah soh lah te doh, the interval between the fah and the te is a tritone.

It is an unlovely interval, so much so that it was shunned in early music, and even abominated as the work of the devil. Its effect is deeply unsettling and disturbing, and Britten uses this effect to stalk us throughout his War Requiem. In war you are always being stalked by the Grim Reaper - as Owen wrote, 'We whistled while he shaved us with his scythe'.

Musical Forces

The War Requiem is scored for a large orchestra with piano and grand organ, with another (smaller) orchestra, a large double mixed choir, a boys' choir with organ or harmonium, and soprano, tenor and baritone soloists. Depending on the circumstances of individual performances, it usually requires two and often three conductors to keep the whole thing together.

As his operas demonstrate, Britten had a sharp instinct for the dramatic - an instinct which is very much in evidence in the War Requiem. Britten intended that the soloists should represent the different sides in the conflict, and wrote for an English tenor (Peter Pears), a German baritone (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who had taken part in the German war effort during the second World War) and a Russian soprano (Galina Vishnevskaya). This reflected Britten's passionate desire for healing and reconciliation between former enemies.

The two men represent soldiers on opposing sides. They are, of course, enemies - or are they? Towards the end of the work Britten incorporates one of Owen's finest poems, 'Strange Meeting', where the two men meet (in Owen's poem the meeting takes place in Hell, although Britten cuts out the reference to Hell) and one says ironically to the other, 'I am the enemy you killed, my friend.' They become reconciled as they sink together into the sleep of death.

Dramatic Presentation

The staging of this work for the concert platform was important to Britten. He wanted the various groups divided into three separate areas or levels. Closest to the audience are the two 'soldiers', who sing entirely in English, and the smaller orchestra that accompanies them. These represent the victims of war. They sing the Owen poems and have the closest rapport with the audience.

Behind them are the main orchestra, soprano and chorus. They represent the establishment, the formal, ritualistic, devout mourners, though their music is anything but staid. The soprano line is always razor-sharp, and she adds an extra dimension to the voices of the chorus, but since they all sing in Latin this is more impersonal singing than the English of the 'soldiers'.

The third level comprises the boys' choir and organ. Britten recommended that this group should be positioned at some distance, even behind the scenes. Their voices are high and remote, floating down to us as if from another world.

Britten wanted the three groupings to be physically separate from each other. He wanted to convey the deafness, blindness and indifference of people towards each other, especially when they are on opposite sides in a war. This aspect is often emphasised in musical terms, especially where different groupings are doing different things in apparent mutual disregard.

The First Performance

Britten and Pears had visited Russia some years prior to the composition of the War Requiem, driving there overland, across Europe by car. This would have been quite a trek in the post-war era, with the condition the roads were in, and the shortage of fuel3. In Russia they met and formed great friendships with people such as the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, the novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, star of the Bolshoi Opera in Moscow.

Thus it was that when Britten came to compose the War Requiem he wanted to write a soprano part specially for Vishnevskaya. She was delighted, but did not feel that she would be able to sing well enough in English, as was Britten's original intention. Still, he didn't want his soprano to sing in Russian and overcame this problem by asking her if she would be happy to sing in Latin. As it happened, this suited Britten's dramatic purpose very well, so this turned out for the best.

When the War Requiem was finished, the score was sent over to Vishnevskaya and she prepared her performance. All was arranged for her to travel to Coventry for the first performance of this prestigious major work. But about ten days before the concert, just as she was about to leave for England, the Soviet authorities changed their minds.

Now all the work put in by Vishnevskaya seemed to be in vain. Britten had the problem of finding a suitable soprano at very short notice who could learn this challenging new music. The ink was scarcely dry on the page, yet whoever took this on would have to perform this highly-exposed part of the Requiem at this major occasion within just a few days.

Fortunately, probably the only soprano around at the time who was able to undertake such a rescue mission agreed to step in and save the day. Heather Harper was the soprano soloist at the first performance, on 30 May, 1962, in the rebuilt Coventry cathedral.

The War Requiem won immediate success and acclaim, and is now performed all over the world. The first London performance took place in Westminster Abbey, on 6 December, 1962.

Recordings

Some eight months after the first performance Vishnevskaya did manage to get to England for the first recording of the work in January, 1963, with Pears and Fischer-Dieskau, and with the composer conducting. That performance remains unsurpassed. It sold more than 200,000 copies in the first five months, an incredible and unprecedented achievement for any classical work of the 20th Century, let alone such a new and difficult classical double-album.

Heather Harper also recorded the War Requiem, in 1991.

Both these recordings were with the London Symphony Orchestra and London Symphony Chorus, and between them they have received a number of prestigious awards such as the Grammy and the Grand Prix du Disque. There are now several other recordings available - but for a truly visceral experience you need to go to a live performance if you possibly can.

During his composing career Britten received many honours at home and abroad, culminating in the honour of a Life Peerage, when he became Lord Britten. He died in 1976.